Highlights: Granite, aplite, pegmatite, mineralisation.

Location: SW 5597 2490

What’s nearby: Loe Bar, Rinsey, Praa Sands

Conservation: Site of Specific Scientific Interest (SSSI). No hammering or collecting at any time.

Information here is provided for reference only. You should ensure that you have permission from the landowner and take safety precautions when visiting sites. Always check tidal timetables before visiting coastal sites and remain aware of cliff falls.

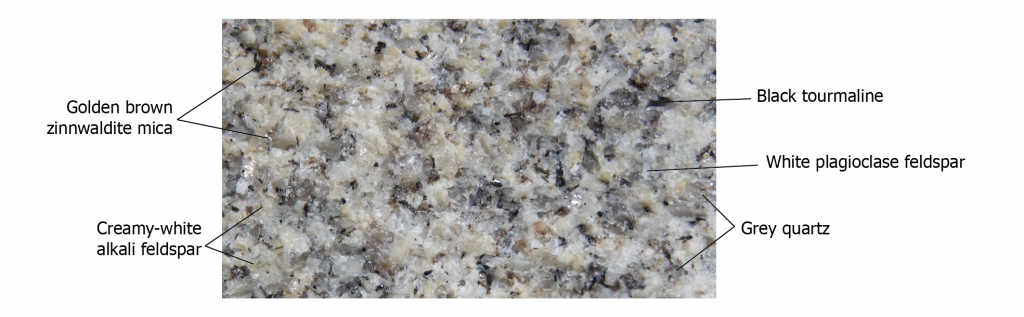

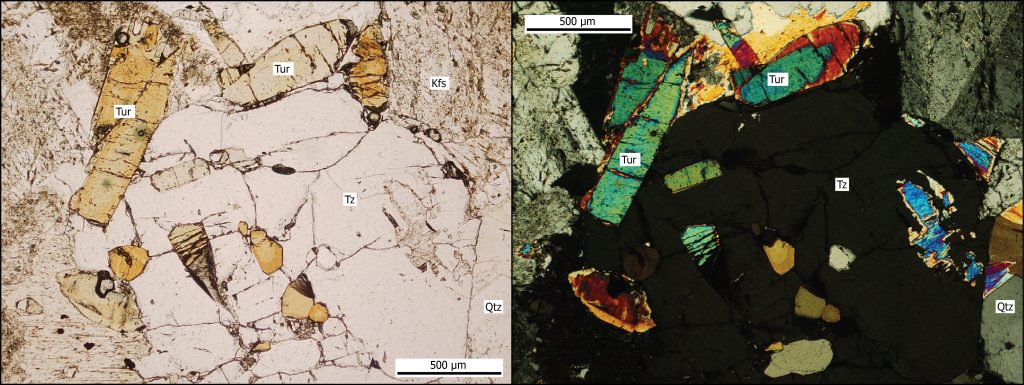

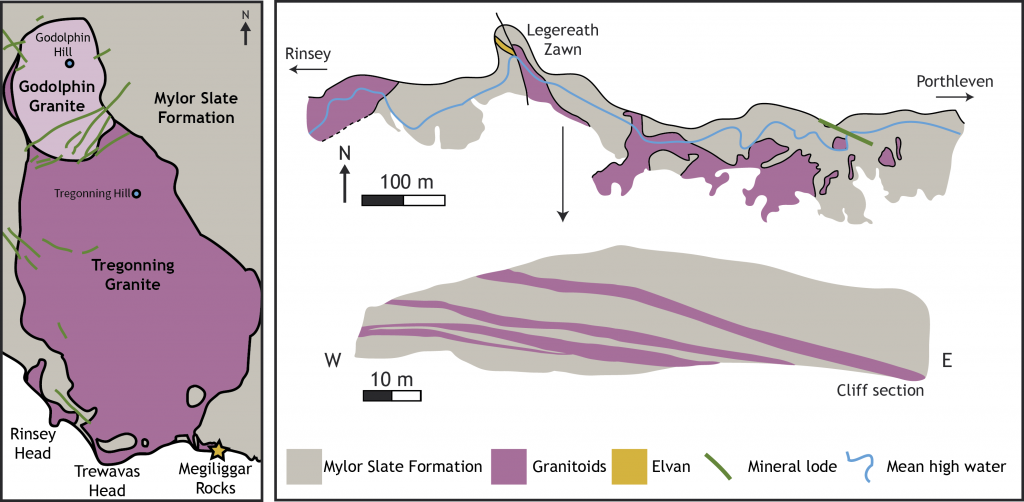

At Megiliggar Rocks, you can find the “roof zone” of the Tregonning Granite, where volatiles (the “stuff” that won’t fit in typical granite minerals) have accumulated. The site has spectacular granite sheets with pegmatite-aplite-line rock extending across the cliff section and an elvan.

Further Reading & References

- Breiter K, Ďurišová J, Hrstka T, Korbelová Z, Vašinová Galiová M, Müller A, Simons B, Shail RK, Williamson BJ, Davies JA. 2018. The transition from granite to banded aplite-pegmatite sheet complexes: An example from Megiliggar Rocks, Tregonning topaz granite, Cornwall. Lithos 302, pp. 370-388. [Link – £]

- Dines HG. 1956. The metalliferous mining region of south-west England. Economic Memoir of the Geological Survey of Great Britain.

- Simons B, Shail RK and Andersen JCO. 2016. The Petrogenesis of the Early Permian Variscan granites of the Cornubian Batholith – lower plate post-collisional peraluminous magmatism in the Rhenohercynian Zone of SW England. Lithos, 260 (1). pp. 76-94. [Link – £]

- Stone M. 1969. Nature and origin of banding in the granitic sheets, Tremearne, Porthleven, Cornwall. Geological Magazine 106 (2), pp. 142-158. [Link – £]

- Stone M. 1992. The Tregonning Granite: Petrogenesis of Li-mica granites in the Cornubian Batholith. Mineralogical Magazine 56 (383), pp. 141-155. [Link – £]