Originally published on allaboutgranite.wordpress.com (previous blog) on the 20th November 2016.

I couldn’t really start this blog without writing about my favourite granite! So what follows here is a bit of a description and a few of my favourite field photos 🙂

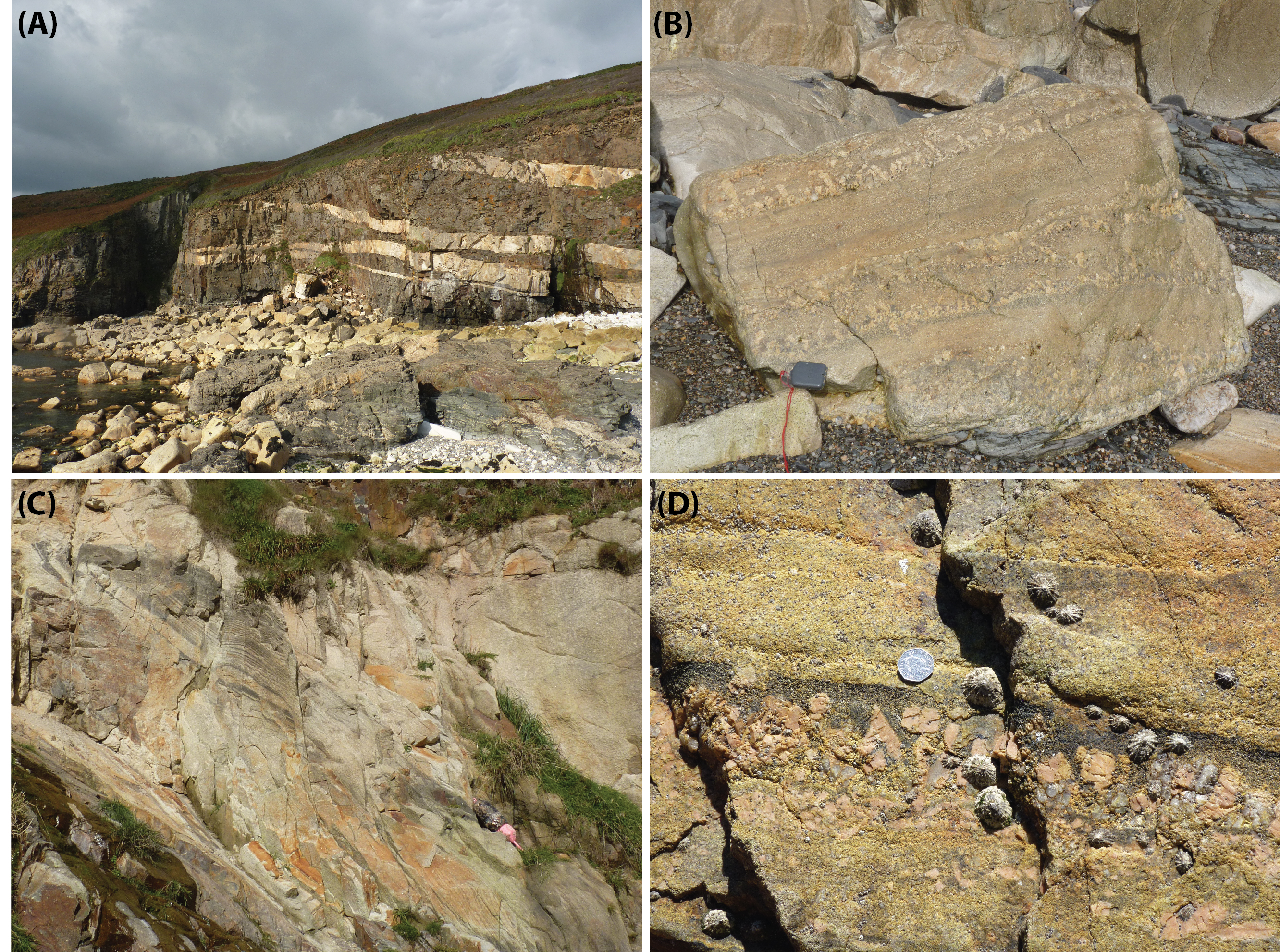

Megiliggar Rocks is located on the south coast of Cornwall, UK and here you can find the coastal exposures of the Tregonning Granite, a minor pluton making up part of the giant Cornubian Batholith. The Tregonning Granite is an Early Permian granite (280 ± 1.3 Ma, [1]) intruded into the Mylor Slate Formation during post-collisional extension at the end of the Variscan Orogeny. These coastal exposures represent the “roof zone” of the pluton where volatiles have accumulated. It’s a really special exposure, encompassing granite, pegmatite, granite sheets and line rock. If you visit, please protect the outcrop, it is a SSSI and no hammering is allowed.

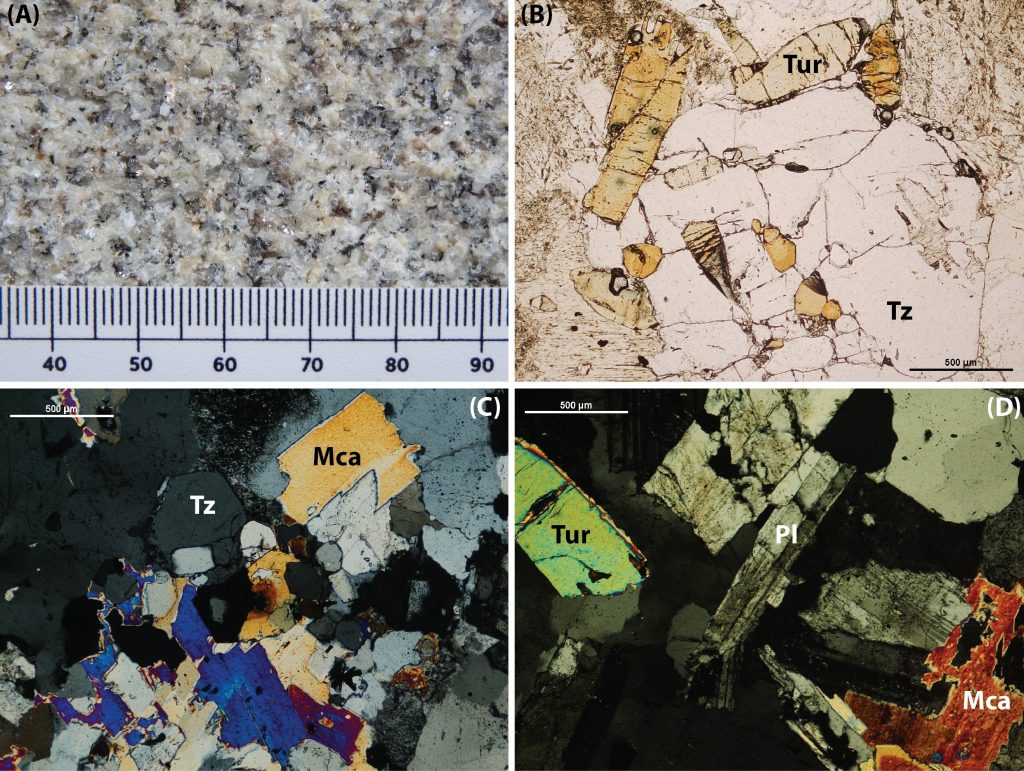

The granite is medium-grained and relatively equigranular with very rare alkali feldspar phenocrysts. Biotite group micas are lithium-rich, zinnwaldite or polylithionite in composition, and plagioclase has a composition of almost pure albite [2,3]. Topaz attains almost 3% modal abundance and therefore the Tregonning Granite is commonly termed a “topaz granite” (logical, huh?). Tourmaline and apatite are common minerals, with rare elbaite pink-green tourmaline occasionally found. Accessory minerals are diverse, encompassing andalusite, amblygonite, Nb-rich rutile, fluorite and zircon. Compared to the rest of the Cornubian Batholith granites, the granite at Megiliggar has higher Na, P, Ga, Nb, Ta, F and Li whilst having lower Fe, Mg and Ti [2].

One of the most spectacular aspects of this exposure are the granite sheets that extend into the Mylor Slate Formation. These sheets dip gently towards the east and extend across the cliff section, narrowing from >1m thick to 10 cm define unidirectional solidification textures (USTs) protruding into adjacent layers. These layered sheets are complex, and don’t have cyclical layers. They appear to have formed from a combination of oscillatory nucleation, undercooling and decompression quenching with multiple intrusive events.

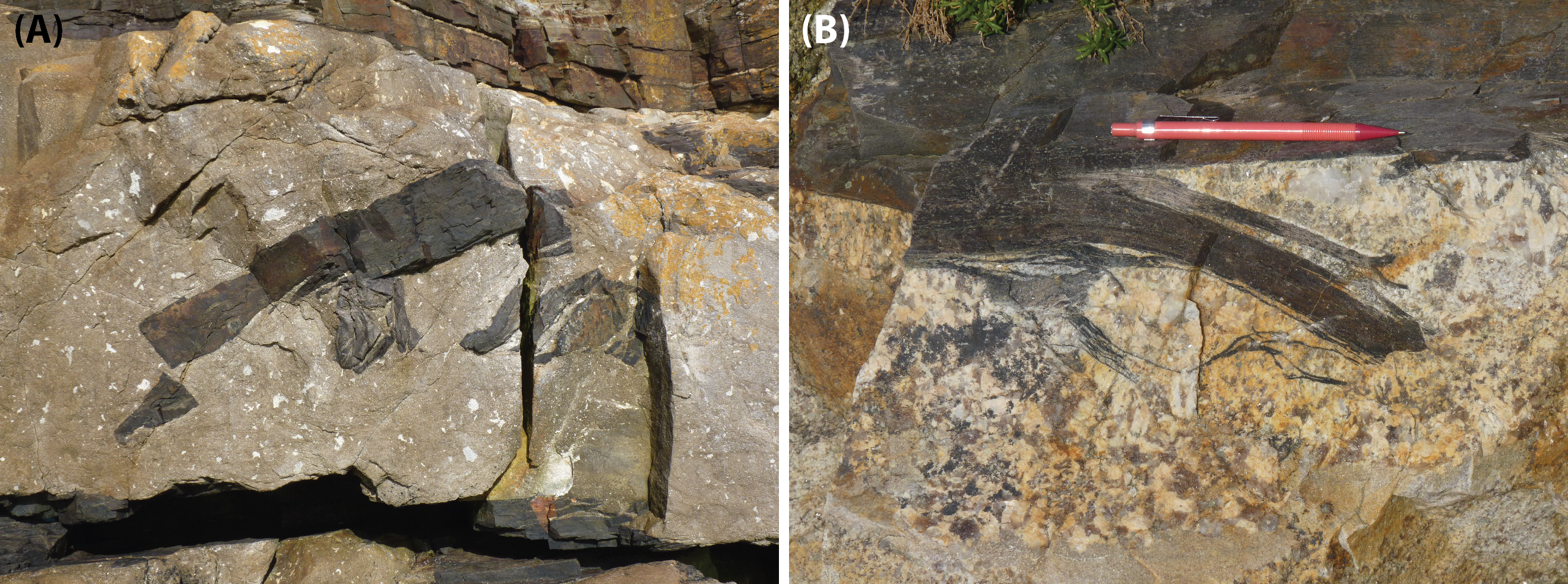

There are host rock xenoliths included within the sheets, reaching >1 m in length and retaining their primary metasedimentary rock structures. There are localised areas where the host rock appears to be peeling off into the granite. Adjacent to xenoliths, comb tourmaline is often developed within a aplitic rim of granite. Occasional “bayonet structures” formed by the detachment of bridge structures between en echelon sheets occur.

References

[1] Darbyshire DPF, Shepherd TJ (1987) Chronology of magmatism in south-west England: the minor intrusions Proceedings of the Ussher Society 6:431-438

[2] Stone M (1992) The Tregonning Granite: petrogenesis of Li-mica granites in the Cornubian Batholith Mineralogical Magazine 56:141-155

[3] Simons B, Shail RK, Andersen JCØ (2016) The petrogenesis of the Early Permian Variscan granites of the Cornubian Batholith – lower plate post-collisional peraluminous magmatism in the Rhenohercynian Zone of SW England 260:76-94

[4] Bromley AV (1989). Field Guide. The Cornubian Orefield. Sixth International Symposium on water‐rock interaction (Malvern, UK). International Association of Geochemistry and Cosmochemistry, 111 p.