In exciting Cornish geology news at the end of 2020, the Natural History Museum, London, announced the finding of a new mineral Kernowite. Named using the Cornish language word for Cornwall – Kernow, the sample was collected over 200 years ago, but had not been detailed as a brand-new mineral species until 2020.

But what does finding a new mineral mean?

There’s an organisation, called the International Mineralogical Association (IMA), who govern the naming of minerals and work to ensure that there is consistency around the world about what different mineral species are called. Currently, there are over 5600 approved mineral species. To name a new mineral it must be proven to:

- Be a natural occurring substance formed by natural processes

- Have a well-defined crystal structure

- Have a fairly well-defined chemical composition

- Be solid in its natural occurrence

However, it’s never quite that straightforward. Take quartz (mineral formula SiO2), which is a simple mineral, with only silicon (Si) and oxygen (O). Quartz has a trigonal crystal structure; it has an ideal shape of a six-sided prism, with six-sided pyramids at each end. However, in granites (for example), quartz doesn’t make this shape, it’s often a kind of amorphous blob with no clear structure at all. Then the chemistry changes – amethyst is a purple quartz, which is purple because it has iron (Fe) impurities in the structure. Citrine, yellow quartz, also has iron impurities and rose quartz has titanium, manganese and / or iron in the structure making it pink. This variation can mean minerals remain hidden, intergrown with others.

The location where a particular mineral species is first identified and described is called the type locality. When naming a new mineral, you can’t name it after yourself and it should end in ‘-ite’ – follow those two rules and you can name your mineral pretty much anything you like (as long as it doesn’t duplicate another!).

Kernowite

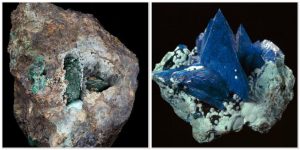

The new mineral Kernowite (Cu2Fe(AsO4)(OH)4·4H2O) is a striking dark green colour and contains copper (Cu), iron (Fe) and arsenate (AsO43-). It’s very similar to another mineral, called liroconite*, which has aluminium instead of iron and is blue in colour; a bit like the quartz structure above containing other metals to make minerals of a different colour, the new Kernowite contained sufficient iron (Fe) to distinguish it from liroconite. Whilst the sample was collected in around 1800 from the Wheal Gorland mine at St Day, it was not described and approved until 2020 – an exciting discovery for mineralogist Mike Rumsey! (*you can “adopt” a liroconite at the Royal Cornwall Museum if you would like to support their collections).

Is this the first mineral discovery in Cornwall?

Many minerals are found in Cornwall, which were particularly well documented during the 19th and 20th centuries when the mines were active. Mindat.org, which is a website that is a treasure trove for all things mineralogy, lists over 500 minerals found in Cornwall. Lots of minerals have their type locality in Cornwall, including:

- Bettertonite ([Al6(AsO4)3(OH)9(H2O)5]·11H2O) – Yes, you are reading the name correctly. It’s a white arsenate (AsO43-) mineral that forms tufts of thin needle-shaped crystals infilling voids in mineral veins. It was discovered at Penberthy Croft Mine in St Hilary and described in 2015.

- Cornwallite (Cu5(AsO4)2(OH)4) – A rare green mineral named in 1846 with copper (Cu) and arsenate (AsO43-) found at Wheal Gorland, like Kernowite. The mine has lots of rare copper minerals formed due to near-surface weathering of other copper minerals.

- Fluroapatite (Ca5(PO4)3F) – a hexagonal phosphate (PO43-) mineral of various colours. This one shares a type locality with locations in Chile and Germany, after it was renamed in 1860 from apatite to fluorapatite to account for the variety with extra fluorine in the structure.

- Lizardite (Mg3(Si2O5)(OH)4) – a brown or light yellow to green mineral of the serpentine group with magnesium (Mg) named for its type locality in 1955 at Kennack on the Lizard Peninsula.

- Russellite (Bi2WO6) – a yellowish green bismuth (Bi) tungstate (WO62-) mineral discovered and described from Castle-an-Dinas tungsten Mine, near St Columb Major in 1938. It is named for the famous mineralogist Sir Arthur Russell, whose world class mineral collection lives in the Natural History Museum, London.

- Stokesite (CaSn[Si3O9] · 2H2O) – a colourless to white copper (Cu) and tin (Sn) mineral named in 1899 that forms amorphous masses as overgrowths on other minerals. Stokesite is named after Sir George Stokes, a mathematician and physicist.

- Stannite (Cu2FeSnS4) – an ore of tin (Sn) with copper (Cu) and iron (Fe). Name from the Latin for tin – stannum, first discovered and described in 1797 Wheal Rock, St Agnes. Stannite is sometimes called bell metal ore because it was used to make bells!

- Tennantite ((Cu,Fe)12As4S13) – a copper (Cu) arsenic (As) mineral, with variable substitution of the element antimony for arsenic in the crystal structure to make the mineral tetrahedrite. Found in many locations including, Dolcoath Mine and Wheal Jane. First described as being from Cornwall in 1817, and named for Smithson Tennant, an English chemist who discovered that limestone reduced soil acidity.

- Tristramite ((Ca,U,Fe)(PO4,SO4) · 2H2O) – a light yellow mineral that infills fractures and voids in mineral veins. It was first described in around 1982 from Wheal Trewavas, near Rinsey and named for Sir Tristram, a famous figure in Arthurian legends.

There are many fab mineralogy websites around, some with wonderful pictures, including Mindat, WebMineral, The Handbook of Mineralogy and the Virtual Microscope, which has a Cornish Mineral Heritage page.

A note on mineral collecting: Many people like to collect minerals but some mineral collectors can be wholly irresponsible doing things like using power tools to destroy outcrops and disturbing bats or nesting birds. If you are interested, join a society, such as the Russell Society who can guide to visit locations responsibly.

References

- Atkin D, Basham IR and Bowles JFW (1983) Tristramite, a new calcium uranium phosphate of the rhabdophane group. Mineralogical Magazine 47 (344), pp. 391-396 PDF – [PDF]

- Grey IE, Kampf AR, Price JR, Macrae CM (2015) Bettertonite, [Al6(AsO4)3(OH)9(H2O)5]·11H2O, a new mineral from the Penberthy Croft mine, St. Hilary, Cornwall, UK, with a structure based on polyoxometalate clusters. Mineralogical Magazine, 79(7), 1849–1858. [PDF – £]

- Hey MH, Bannister FA, Russell A (1938) Russellite, a new British mineral. Mineralogical Magazine 25(161) pp. 41-55 [PDF – £]

- Hutchinson MA (1899) LII. On stokesite a new mineral from Cornwall, Philosophical Magazine Series 5, 48(294), 480-481, [PDF]

- Nickel EH, Grice JD (1998) The IMA Commission on New Minerals and Mineral Names: procedures and guidelines on mineral nomenclature. Mineralogy and Petrology 64, pp. 237-263 [PDF – £]